Resource Efficiency

While efficiency is a word commonly used in the realm of waste, it does not always refer to the same concept. Material efficiency and economic efficiency don't always line up perfectly, but innovation can help bridge the gap. Understanding the trade-off between adding more efficiency and the cost it brings is key, as pushing too hard for efficiency can sometimes waste more resources than it saves. Simple economics and smart thinking are needed to avoid common traps and make sure waste management efforts are truly beneficial.

Material & Economic Efficiency

The discussion of efficiency in any industry, especially in waste management, often brings to light two key concepts: material efficiency and economic efficiency. While related, they mean different things, aim for different outcomes and interact in complex ways.

- Material efficiency focuses on optimizing the use of materials. This form of efficiency takes an engineering perspective, focusing on minimizing material losses in materials and energy throughout operational processes. The ultimate aim is to maximize use of every unit of material. This concept does not contemplate cost-efficiency, but rather technical viability.

- Economic efficiency is about maximizing value and utility in the market. It's not limited to physical resources but extends to all resources, including financial resources and human capital. This type of efficiency evaluates decisions based on economic benefits relative to costs. Here, the primary objective is to maximize profits, considering market dynamics, consumer demands, and cost-efficiency.

The alignment between material and economic efficiency is context-dependent. Sometimes an increase in material efficiency brings economic efficiency, leading to cost savings or improved market competence. However, in other cases, striving for maximum material efficiency can lead to increased costs that outweigh economic benefits. Conversely, the pursuit of economic efficiency may lead to choices that aren't materially efficient but offer greater value.

Bridging The Gap Through Innovation

Innovation is pivotal in aligning material and economic efficiencies. Achieving higher material efficiency requires balancing costs and benefits. Technological and methodological innovation can significantly reduce these operational costs, thus improving the economic feasibility of processes aimed at higher material efficiency.

Example: automated waste sorting systems can reduce associated costs, making the process of recovery more economically viable. This aligns the benefits of recovering resources more closely with their operational costs, potentially turning what was once an economically unfeasible activity into a profitable one.

Marginal Gains and Costs

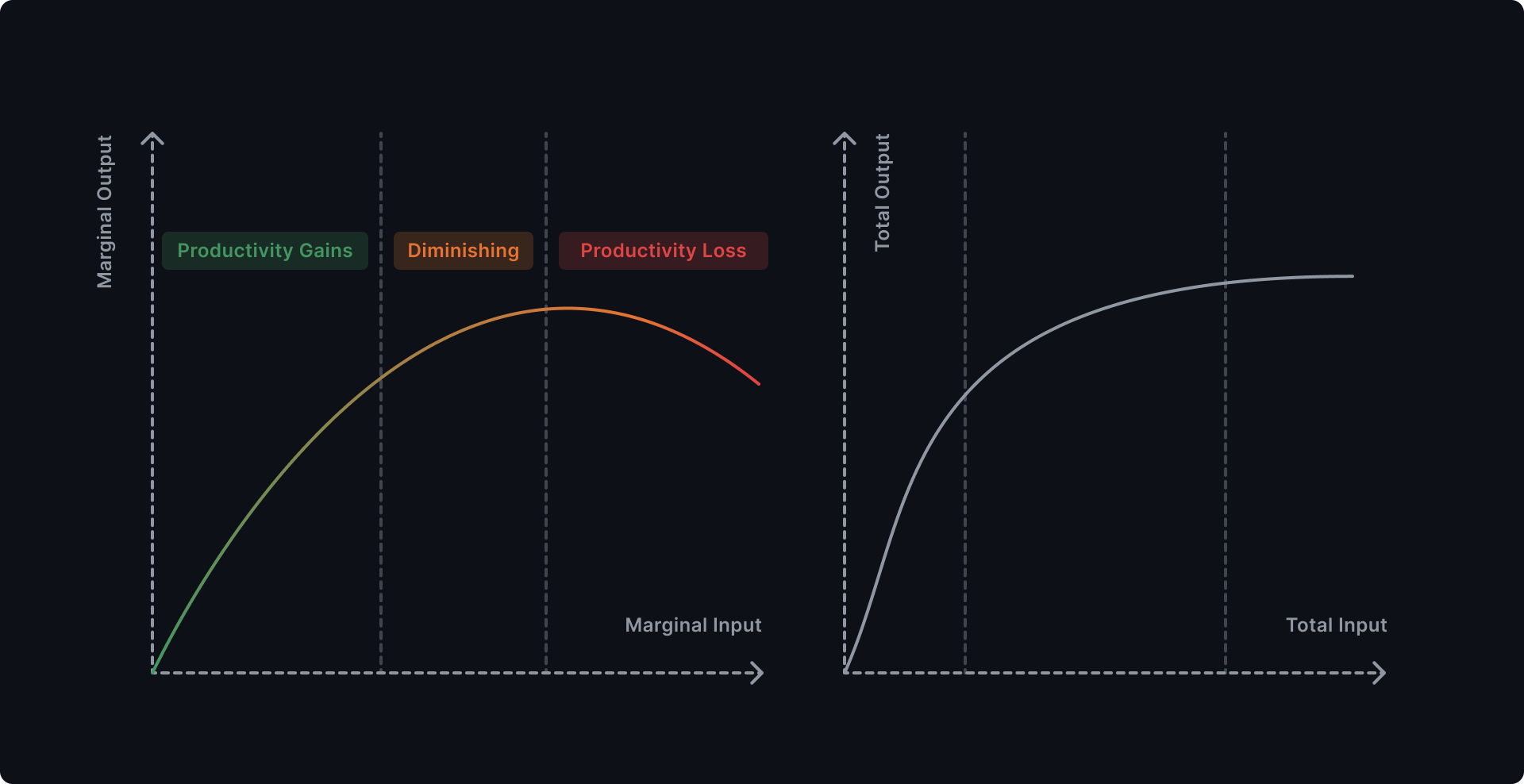

The concept of marginal benefits in material efficiency relates to the additional gains obtained by improving material efficiency by one additional unit. Initially, improvements in material efficiency yield significant economic benefits. Yet, as efficiency levels increase, the cost and complexity of achieving further improvements escalates. This phenomenon reflects the law of diminishing returns, where each additional step towards greater material efficiency demands more resources.

Beyond a certain point, each increment in material efficiency requires an increasingly larger investment of resources. These investments can include advanced technologies, changes in waste processing operations, or more intensive labor inputs. While each of these increments contributes to material efficiency, the marginal benefits—additional economic or environmental value created—begin to decline. This diminishing return raises critical questions about the optimal level of material efficiency, where the additional value created is balanced against the resources expended to achieve it.

Marginal gains and costs in material efficiency underscore a pivotal realization: there is a threshold beyond which efforts to enhance material efficiency counterintuitively undermine it. Crossing this threshold means that any further attempts at improving material efficiency result in a net economic loss, meaning that the resources required for such improvements, manifested as costs, outweigh the resources that can be saved, expressed as benefits. This critical juncture highlights the delicate balance required in pursuing sustainability goals—where the pursuit of material efficiency must be judiciously measured against its economic implications. Recognizing this constraint is essential for ensuring that efforts to improve material efficiency do not inadvertently deplete more resources than they save.

Efficiency Misconceptions

While most environmental arguments usually disregard economic efficiency as a mechanism to drive resource allocation decisions, it is also true that market dynamics can be affected by forces like monopolies, flawed regulations or information asymmetries that may affect their efficiency. These common pitfalls in logic can drive innovation in senseless directions. By reasoning from solid ground principles, such misconceptions can be clarified.

-

Disregarding Economics. Advocating for material efficiency regardless of the economic implications can lead to a net loss in resource value. While the intention to preserve resources is commendable, this kind of argument undermines the fact that economic costs are representations of other resources. Ignoring this reality can lead to promoting actions which consume more resources than the value they create.

The Case of Low Value Plastics

While recycling is often advocated for environmental benefits, the process of recycling certain low-value plastics can be economically unfeasible. The costs associated with collecting, sorting, cleaning, and processing these plastics often exceed the value of the recycled material. For instance, recycling plastic films or certain types of food packaging might consume more resources in terms of energy, labor, and financial expenditure than the value they create as recycled products. This leads to a net loss in resource value, demonstrating that recycling, while materially efficient, can sometimes be economically unsustainable, thus leading to an overall loss in resources.

-

Market Inefficiencies. Market prices can sometimes be skewed by factors like monopolies or regulatory loopholes, leading to inefficiencies. This is an argument for refining regulatory frameworks rather than discarding market prices as a decision-making tool. Even imperfect, prices provide a crucial indicator of resource value and should be used judiciously to guide resource allocation decisions.

Understanding E-Waste Exports

In some regions, the recycling of e-waste is less economically attractive due to regulatory loopholes. For example, it may be cheaper for companies to export e-waste to countries with lower environmental standards due to differences in tax structures or environmental regulations. This practice can lead to a situation where, despite the inherent value in recovering materials from e-waste, the economic incentives favor exporting waste rather than recycling it locally. Regulatory loopholes can distort market efficiency, leading to decisions that undermine the potential for recovery and proper waste management.